John Berresford's Story...My Testicular Cancer |

|

|

| |

This is the story of my testicular cancer.

The

only things you need to know about my earlier life are that I came

from a wealthy Puritanical family and that, in 1981, I had barely

spoken to any of them for several years. Partly for that reason,

those years had been the happiest of my life. About a year before, I

woke up to the fact that I was gay and was playing the field with

enthusiasm. I was a 31-year old successful lawyer in Philadelphia,

specializing in litigation for the telephone company. One day in the

fall of 1981, I passed a prominent Judge on Broad Street and he

bowed his head as we passed. I took this as a compliment. As I

continued my walk home, I said to myself “I’m only 31 and I already

have judges bowing to me. I’m bored. God, if you exist up there,

send me a new challenge.” The

only things you need to know about my earlier life are that I came

from a wealthy Puritanical family and that, in 1981, I had barely

spoken to any of them for several years. Partly for that reason,

those years had been the happiest of my life. About a year before, I

woke up to the fact that I was gay and was playing the field with

enthusiasm. I was a 31-year old successful lawyer in Philadelphia,

specializing in litigation for the telephone company. One day in the

fall of 1981, I passed a prominent Judge on Broad Street and he

bowed his head as we passed. I took this as a compliment. As I

continued my walk home, I said to myself “I’m only 31 and I already

have judges bowing to me. I’m bored. God, if you exist up there,

send me a new challenge.”

The following Monday, November 12, I decided finally to attend to

something that had been bothering me more and more. My left ball has

been growing slowly hard and larger than the right one. The leftie

was about the size of a golf ball. There was no pain in urination or

ejaculation, and none of my boyfriends or one-offs made a comment

about it, so I figured nothing was wrong. But I decided to see my

doctors (a group at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital) anyway. A

young doctor felt it and said that it couldn’t be a pinched nerve

because they are “exquisitely painful.” He sent me to a urologist

across the street.

The urologist saw me the next day (I understand that in some

‘socialized medicine’ countries, you wait months to see a

specialist. Had I been in such a system, I would have died around

the end of 1981.) He was a short, middle-aged man of Australian

extraction, with a trim mustache. He reminded me of the Col.

Nicholson character played by Alec Guinness in The Bridge Over the

River Kwai. He interviewed me and took a urine sample. Then he

proceeded to feel up my left ball for a few minutes as we talked

about everything except the fact that another man was feeling up my

left ball in the middle of a workday. Then, in his trim accent, he

said calmly said “Well, John, I’ve felt it long enough. I know what

it is. It’s a tumor and it’s got to come out.”

I could not have asked for bad news to be stated more gently and

effectively.

When he said “tumor,” I immediately thought of cancer – a word that

connoted death much more in 1981 than it does today. I figured that,

in order to get the unvarnished truth from him, I had to appear

calm. I asked, “Does this mean I have cancer?” He gave me a lengthy,

roundabout, incomprehensible answer, which I took to mean “Yes.” I

asked him “What is the survival rate?” He answered that there were

three kinds of tumors. Most of them were seminomas, the second most

common was embryonal cell tumors. They both have survival rates of

about 80%. Then there’s a third kind – I recall that its name ended

in “oma” and that it amounted to about 10% of the cases. He said

something that politely conveyed that the third kind of tumor was

fatal. I was surprised to hear him say that he would not know what

kind of tumor mine was until they cut me open and looked at it. Gee,

maybe doctors don’t know everything.

I asked him what might have caused this. He said it happens to

otherwise perfectly healthy young men between 18 and 35. It’s been

linked, in a small percentage of cases, to a fertility drug that was

in widespread use in the early 1950s. That was not my case.

I then asked the doctor “What puts you in the 80% or the 20%?” He

said it was hard to predict. He noted that I’d told him I jogged and

worked out a lot, and he said that he’d observed that testicular

cancer occurred in a lot of people who are very physically active:

“I’ve done a lot of surgery on footballers.” (Please note: I

received different answers from each of my oncologists. One said

that the most important factor was the patient’s attitude. The other

said that if action was taken before cancer reached your lungs or

brain, you would survive; if it had reached there, you should start

putting your affairs in order.)

I asked the urologist if he would cut open my scrotum and remove the

ball. He said no. If you do that, the trauma for the scrotum is so

great that the remaining ball withdraws into your torso. Each ball

is connected to a sort of string that goes up into the torso. We cut

at the line where your leg meets your torso, pull the string, and

the string and the cancerous ball come out.

The urologist told me that, based on what little we knew, survival

was the likeliest future. But he made no prediction about my case.

He added that, even if the long run prognosis is good, the next six

months are going to be really rough. We’re talking about two, maybe

three major operations, and then chemotherapy or radiation therapy

depending on what kind of tumor it is, and those are really rough.

The urologist told me that he’s remove the tumor on Thursday morning

and I should check into Jefferson University Hospital Wednesday

afternoon. (Philadelphia is a good place to be seriously ill, by the

way. I read that 15% of all the MDs in the United States got their

medical degrees there.)

I recall having some blood tests and X rays. I don’t remember

exactly when they were done. My recollection of what they showed may

be wrong after all these years, but I recall that (1) the X rays

showed that the cancer had not spread to my lungs or my brain (good

news), but (2) the blood tests showed me with a very very high

amount of cancer, several times more than what was usually fatal.

So, go figure.

I went back to work. I had never been seriously ill and had no idea

whether my insurance (Blue Cross Blue Shield of Pennsylvania)

covered cancer. The office manager told me it did. Because I was

squeamish about testicular caner – a few hours before I had not

known there was such a thing – I told the manager I had stomach

cancer. Maybe this alarmed her, because it was fatal back then.

I also told other people in the office, a few of my best friends,

and my older brother (the only family member with whom I was on good

terms). One friend who knew some doctors called me back soon and

said that, if you have to have cancer, testicular cancer is the kind

to have.

I called my boss to tell him that I had cancer. When I began talking

about my work, he cut me off. He told me that until I was completely

well I should forget that I had any obligation to my job. Take off

all the time you need and, if there is ever a bill that Blue Cross

won’t pay, send it to me and I’ll see that it’s paid. I will never

forget that.

My emotional state was numb. I was not raised to have feelings or to

express them. Perhaps that was helpful in this experience. I was

numb partly, too, because the cancer diagnosis was so new and

unexpected. I had not given a moment’s thought to dying at 31 (AIDS

was just a blip on the horizon, only people in New York and San

Francisco got it). I didn’t even know you could get cancer in a

testicle. I was (and still am) self-reliant and not given to

self-pity or fear. My childhood had taught me that life is sometimes

awful and unfair, but that surviving those times is what gives life

depth and meaning.

The greatest regret I had about going into the hospital was that I’d

have to put my Springer Spaniel, Sarah, in a kennel. The greatest

fear I had about death was leaving her alone in the world.

I bought some pajamas and checked into Jefferson Hospital Wednesday

afternoon. The next morning, no breakfast, a couple of shots, onto

the gurney, and into the operating room. The surgeon bustled in,

bent over to look me in the face and chirped “Good morning, John,

how are we today?” There may have been a small joke about being sure

to remove the LEFT testicle – which is probably why he greeted me by

name, to be sure exactly who I was: Berresford, remove the left one.

The next thing I remember the operation was over and I was back in

my room. Sharing the room was a speechless old man who had had a

serious stroke. I remember very little of the next few days, except

for a couple of phone calls and watching daytime TV. (Philadelphia

did not have cable TV yet – the City Council members had not agreed

on the form and amount of the graft.)

I recall the surgeon telling me that blood tests showed 80% of the

cancer gone. He also said I had had an embryonal cell tumor.

One evening I was still in the hospital and getting used to having

only one ball. I was listening, on an early Boom Box, to a London

Symphony Orchestra performance of Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony,

one of my favorites. At the slow, joyous coda, which takes about a

minute, I began crying and suddenly felt a tingling in my scrotum

where my left ball had been; it slowly spread over my whole body.

When the music ended, the tingling ended. I felt, suddenly and deep

down, that everything was going to be OK. (I did not take this as a

sign that I was going to survive. I might die, but that would be OK,

too.)

More thoughts occurred as I recuperated from the first operation.

Maybe I’m going to die a lot sooner than I expected. I’d always

wondered what came next (I thought something did), and now I’m going

to find out soon. Great, if that’s what’s going to happen. In one

sense I wanted to live, but in another I began preparing to leave

this world in contentment. One thing I was surprised happened was a

growing, and finally total, indifference to everything in this

world. It’s hard to describe. The best I can do is that I felt like

my present life was a book that was closing. I saw myself as a

little man reading a huge book by walking along one line after

another and reading the words. This book was my life and, well, it

turned out to be a lot shorter than I had expected. It was closing;

the cover was about to slam shut and I’d better get out of the way.

But nearby another book was opening – the next life. I could hardly

wait to see what was in it. Would I see my Grandparents again? Would

I get to know my Father (who died when I was 3)? One thing that

always puzzled me – if he looks the way I can recognize him, how

will his friends from childhood recognize him?

My oldest friend and my brother came down from New York City to take

me home Saturday at noon. (I lived in a small house a few blocks

from Jefferson Hospital.) That morning I decided I didn’t want them

to be nanny-ing me, so I walked home myself, started a fire in the

fireplace, iced some champagne, and met them at the hospital. We

walked home and then to a restaurant near the Delaware River.

When they left, I got Sarah out of the kennel. When she and I were

back home, I undressed and got into bed under the covers. Sarah got

up on the bed with me and placed her head exactly where the Doctor

had cut me. She knew, she cared.

I was back at work the next Monday. Sitting down, sanding up, and

walking produced a sharp burning sensation along the scar, but it

was tolerable and lasted only a few seconds. It was worth the pain

to sit down, to stand up, and to walk around – to be part of the

world.

Everyone was very sympathetic; great people. The phone ‘rang off the

hook,’ and my mailbox was full, from people I had not spoken with in

years wishing me well. Some said they had even cried when they heard

I had cancer.

Some weeks later I was able, without too much pain, to ride the

train up to New York City and have Thanksgiving Dinner with friends

at the Plaza’s Oak Room. It was a great Thanksgiving. I had little

idea what lay ahead because the whole experience was still so new to

me.

The only sad-making thing was that a very handsome and charming guy

whom I had dated three times (we’d had sex once) dumped me instantly

and totally. I ran into him on the street and he told me he’d been

busy, but I suppose he was just frightened of cancer. We’d only been

on three dates, after all, too. Maybe I was just a roll in the hay

to him – there are worse things to be – and cancer was too serious.

He wanted a hot date, not melodrama. It hurt, but I can’t blame him.

Generally, I found that all my human relationships changed. People

either got much closer to me or ran away as fast as their legs would

take them. And who fell into which group surprised me. On the whole,

there were more people who got close than who ran away. The latter

group – to hell with them, they were going to run away from me

someday.

Three weeks later I was back in Jefferson for the second operation.

It was supposed to be mopping up exercise, cleaning up the little

cancer that remained in the groin area. I was rather blasé about the

whole thing. Again, the operation was early on a Thursday morning

and began early with a chipper greeting from the surgeon. I remember

expecting the operation to be over by 10 am at the latest.

When I awoke, I saw the surgeon’s face close to mine, his hair

covered in a shower cap. He said “Well, John, we found a lot more

cancer that I expected, but I think we got it all.” I thanked him

and he went on to his next operation. They wheeled me into my room,

lifted and moved me onto the bed, turned out the light, and left me

alone. I called my brother, got his wife, and told her the good

news.

It was the early afternoon – this had been no mopping up operation.

I fiddled with the controls on the bed and raised my torso so that,

if I turned my head, I could see out the window onto Chestnut

Street. I was on the second floor of Jefferson’s new wing – where, I

later learned, they sent you if you were really sick. Through the

window, I saw a boring urban in the powdery yellow light of a

December afternoon. A man in a heavy overcoat was walking into the

wind, with his head on his porkpie hat to keep it from blowing off.

I said to myself “How beautiful that is” and went to sleep for a

long time.

I had a catheter up my penis, an IV drip in one arm, and a tube up

my nose and down to God knows where. Until Sunday night, I received

a shot of Demerol every four hours. Each shot made me indescribably

comfortable. Three hours after each shot, any movement brought sharp

pains all over my torso. Under demerol’s influence, I saw colors

that I have never seen since and had dreams of short jerky movements

that I have never had since and that are physically impossible. Also

every few hours a nurse walked in and used a kind of bellows on a

tube that entered my nose. She drained my stomach and spleen (or

another organ) of fluids. One organ’s fluids were green and the

other was blue, I recall. The colors, the jerky dreams, the green

and the blue are about all that I remember of the next few days –

except for the lovely, dreamy effects of the demerol. Two friends

visited me, without invitation, and left me with “a box of

feelings,” which I found silly to put it politely. All I remember

saying to them is that I couldn’t wait to get all the tubes out and

back home. After leaving my family, I had composed a job, a life, a

home, a circle of friends, a dog, and hobbies that I loved. I just

wanted to get the hell back to them.

A few other memories of my recovery from what one doctor called “The

Big Zipper” surgery. My torso was covered in gauze and bandages that

stretched from my neck all the way down to the base of my penis. A

few days after the operation, a movement I made caused this

breastplate to popup a bit, and I looked down. I gasped. What I saw

was a red line (the surgical scar) with black stitches across it,

stretching from my sternum to my crotch. The distance seemed to me

the length of a football field. After I admired the a lovely detour

around my belly button, it sank in on me how much trauma my body had

been through.

Second, on Sunday I made the bold and slightly insane decision to

take a shower. I am meticulous about my appearance, and I had not

washed my hair in days! Somehow, and I suppose at great risk to the

containment of my organs, I managed to move all the tubes my IV pole

and then I moved my body to the bathroom, gave myself a short

shower, replaced the IV and nose stuff in their former locations,

moved my cleaned body back to the bed, and popped the gauze

breastplate back on. I suppose much of me might have spilled all

over the floor, but my hair looked presentable again. And I had done

something, not just lain there like a sack of potatoes.

The surgeon visited me one day and said that blood tests had shown

that the second operation has removed all but 2% of the cancer I had

when I first saw him. He said that he made an incision near the top

of my penis and first removed the lymph nodes closest to the

cancerous testicle. He sent them to the lab down the hall and they

tested them for cancer. They reported back to him that there was

cancer in the lymph nodes. So, he cut a little higher, removed the

lymph nodes, sent them down the hall, and so on. He said that the

lymph nodes around my spleen were so mushy that he could have

removed them with a spoon. I recall him also saying that the lymph

nodes around my aorta were about to start damaging that essential

pathway. It seemed to me that perhaps I would have died had the

operation been a week later. He said that he reached the point where

the only way he could cut higher was to break open my rib cage. He

figured I’d had enough for one day, and stopped.

He said that I was well into Stage 2B of the disease. 2% of the

cancer that had been in my body was still there, and it was likely

diffused all over, so I would need chemotherapy.

After a few days my digestive organs got over the trauma I could

take Jell-O and yogurt. One day I lunched on a chicken breast – a

whole chicken breast!! Half an hour later, I thought my stomach was

going to explode. It didn’t.

Not long after that, the first of my two chemo doctors came to see

me. We had a pleasant conversation. He said I’d have two long stays

for chemo, about 10 days each, separated by a month or so to

recover, and then, after another month to recover, one weekend of

chemo at the end. He may have told me about what chemicals were

going to be put in me, but I have forgotten. I asked him what the

side effects were. He said that they didn’t like telling people

because the side effects were so many, some of them were really

horrible but almost never happened, and telling people more often

than not just scared them out of their wits. He said that

chemotherapy kills off whatever is growing fast inside you, and that

includes cancer and, typically, hair and the lining of digestive

organs. So, the most typical side effects, other than killing

cancer, are hair loss and nausea. But the side-effects are

temporary, he said; the hair, for example, starts growing back

immediately. I let it go at that.

I left the hospital, walking home again and greeting my brother and

oldest friend in my “I don’t need your help” manner. And, in fact, I

didn’t. I have found that asking for help when you don’t need it is

a slippery slope to parasitical dependence. I also learned that the

world is full of people who want others to be dependent on them.

These people want to convince you that you need them so they can get

their hands in your wallet or, if you’re cute, in your pants. This

was obviously not the case with my brother or best friend, but I

also sensed that if anyone were camped outside my hospital room

“helping” me all the time, they might die of boredom and I would

certainly die of exhaustion.

With my brother and oldest friend I lunched at a wonderful French

restaurant called Deux Chiminées. I ordered duck breast and, when I

could only get one down, asked for a doggie bag. The waiter asked if

there was something wrong and I replied no, I was just out of the

hospital after major surgery on my abdomen and I wanted to save it

for later. This started another bit of kindness from strangers. The

people at that restaurant saw me through the next months of hair and

wait loss and always asked after me with sincere concern and gave me

their best wishes.

I returned to work the next Monday. It took me 25 minutes to walk

there instead of the usual 15, but I made it. I found that sitting

at a desk writing on paper, with my torso and upper legs forming a

90 degree angle, gave my scars and stitches a chance to contract.

So, when I stood up, I would walk crouching over like Groucho Marx

for a few minutes. Some of my colleagues laughed at me and I joined

in on the laugh.

One night I rolled over in bed for the first time. Holy hell, I felt

all my innards sloshing around and, for a moment, thought that they

might all over the floor. But they didn’t. And all the muscles on my

sides that had been holding me together since the second operation

cried out “Thank you!” in blissful relaxation.

I had a post-operative consult with the surgeon. He asked me to

undress and I noted, bashfully, that I was wearing red bikini

underwear. When he saw them, he exclaimed “Ah, Christmas-sy!”

For Christmas, I took the train up to New York and dined again at

the Oak Room at the Plaza.

My chemo was supposed to begin shortly after New Years Day. A few

days before, the hospital called me and said that no one goes to the

hospital between Christmas and New Years unless they absolutely

must. They said that if I checked in for the chemo before New Years,

I could get a private room. I packed a bag and was there the next

day. Bring on the chemo!

At first it was anticlimactic. No side effects except maybe a little

fatigue by the end. That, however, could have resulted from being

limited for ten days to staying in bed or walking around the floor

with my IV pole. People from the office visited during lunch hour.

Once two office mates called me and asked me if they could bring me

anything. I asked for 4 Size D batteries because my tape player (aka

Boom Box) was losing oomph. Another evening, my interior decorator –

not a close friend – came by. He got himself a little dinner at the

cafeteria and sat in my room for an hour talking with me about this

and that. He didn’t have to do that. Funny how we remember little

acts of kindness like that.

Lots of friends called from California. Sadly, one of them died of

AIDS not much later. I called him frequently and sometimes felt

‘survivor guilt’ as daily I got better and he got worse.

Although I never sank to watching The Love Boat, I did begin

watching a lot of daytime TV and nighttime movies. On New Years Eve

the nurses and I toasted in 1982 with a bottle of Mums champagne,

which we drank from Styrofoam plastic cups.

On the second to last day of my stay (about 8 days into the whole

stay), no dinner. In the early morning, the nurse walked in with a

tray covered with a handkerchief. She removed it and revealed about

six syringes. They ranged from small to cow-tranquilizer size. I

asked he what they were and she rattled off some names, including

‘steroids,’ a word I’d never heard before. When she had hooked up

the cow-sized syringes to my IV tube, she pushed the contents in

with the heel of her hand shaking.

I was given a pitcher and told to drink large amounts of water. When

I reached a flow of water in and urine out approximating the

Delaware River, they hooked a bag of liquid platinum (cisplatin)

onto my IV tube and it began dripping into me. The platinum looked

like scotch, the same shiny gold-brown color. It was in, and

somewhat out, out in half an hour. About an hour later I began to

feel cold in my stomach. I sneezed a few times. Then there were a

few dry heaves, but nothing much to vomit up. I think it was the

next morning I went home and followed the routine: Sarah out of the

kennel, buy groceries to restock the fridge, and back to work the

next morning.

A short time later I got a call at the office from the senior chemo

doctor. He said that blood tests had failed to detect any cancer in

my body. Not sure what exactly he was saying (the news was so good)

I thanked him and hung up. I thought for a minute. Then I called him

back and asked “What you told me a minute ago – did that sound as

good to you as it did to me?” He said “Yes, there were a lot of

people here who were very happy.” I said, slowly and softly, “Hot

damn.” And began calling fellow workers, my boss, and friends.

Some of my not-best friends were convinced I had AIDS (I’m not sure

it was even called that yet). They were elated to find out I had

cancer. Great celebrations: “John has cancer. Hooray!!!” One of the

many ways this was an hilarious experience.

Anyway, all cancer gone, no hair loss, no weight loss. Maybe I’ll

beat it, and with no side effects!

A lady I worked with had had breast cancer a year before and she

recommended a shampoo that, she thought, had something to do with

her not losing any hair. I began using that shampoo.

About a week later I was washing my hair in the sink and noticed

that the sink had not drained. I stuck my hand in the gray water and

pulled out a baseball-sized ball of hair. Well, it’s begun, I said

to myself. Hair began falling out on my desk, in my food,

everywhere. The scalp hair fell like rain, mustache hair not at all,

the rest of my hair (chest, legs) slightly. Tight jeans were the

style then and my legs were soon hairless. In a few days I was bald

on top and thinning everywhere else. I went to a neighborhood hair

place, and said “What do I do?” The nice guy there said he’d shave

it all off, which he did in five minutes and at no charge. He said

to come on back any time, no charge, when the hair came back.

Another unexpected act of kindness.

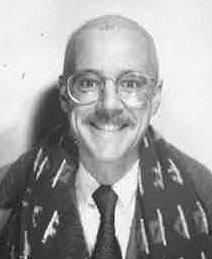

One

friend said that, without hair, I looked like a fifteen year old

angel. I thought that, with my mustache and wire-rimmed granny

glasses, I looked like the mad scientist Albert Dekker in the 1940

sci-fi film Dr. Cyclops. One

friend said that, without hair, I looked like a fifteen year old

angel. I thought that, with my mustache and wire-rimmed granny

glasses, I looked like the mad scientist Albert Dekker in the 1940

sci-fi film Dr. Cyclops.

A few weeks later, and my second long, “blitzkrieg” of chemo began.

Same chemicals as before, same second floor of Jefferson’s new wing.

I think it was during this stay in Jefferson that I shared a room

with the owner of a grocery store who had stomach cancer. I’ll call

him Joe. One day Joe had just lost his appetite and stopped eating.

Surgeons opened him up, saw massive stomach cancer (which then was

virtually incurable) and sewed him up again. There was nothing they

could do except chemo to maybe undo it a bit or slow it. Either they

didn’t tell him the prognosis or he didn’t hear it. He was immobile

and always terribly thirsty. We had a lot of chats, especially at

night, in which he went on and on about how “these doctors” can’t do

anything and how thirsty he was.

Frequently he was visited by his wife and kids, other family members

(one of whom was the realtor who sold me my house), and employees at

his store. They really liked him. They kept encouraging him and he

kept telling them how thirsty he was. What struck and saddened me

was his complete lack of spiritual life, the absence of any

invisible comfort. I wished I could have given him some of mine,

wherever it came from. By any standard of usefulness to other people

and having people in life who loved him, he was living a better life

than I was. In a just world (by my lights) he should have lived and

I should have died, but it looked like the opposite was going to

happen. He died not long after I walked home. From time to time in

the next few years I would pass the realtor in the street, say

hello, and ask after the man’s widow. The realtor would tell me a

little news and say how good I looked. I wondered how Joe looked.

Another case of survivor guilt.

I recall a few things about that stay other than Joe. One day my

temperature shot up to 104. One of my chemo docs came by quickly

(thank you, Doctor!) and they cut my dosage of bleomycin. I told the

doc that I’d be willing to have a 104 temperature if it would

improve my chances of survival. But he said ‘no sweat.’ Another day

I was walking along the hallway with my IV ball and chain and I met

my former secretary and another work colleague, both there to visit

relatives who were not doing well. They had not heard I had cancer

and were appalled that I was on that floor, which they took as a

death sentence.

A few doors down from me was an elderly lady; every morning when I

walked past her room I saw her son, middle-aged, spoon-feeding her

breakfast. That’s love, I thought.

One night, as I was walking the halls with my ball and chain, I had

a chat with a nurse. She told me “We’re not supposed to say this,

but your file says ‘Prognosis: Excellent.’ I noted that things

didn’t seem so hopeful for Joe. She nodded sadly. Thinking of my own

case and the remaining possibility that I would die, I asked her

what they do when a patient is incurable and doesn’t want any more

chemo. She replied that they put “DNR” on their file, Do Not

Resuscitate. Then, cleverly moving one step at a time, I asked –

what if I knew I was going to die in a month or so and just didn’t

want to linger here watching re-runs on TV and crapping on rubber

sheets 4 times a day. Oh, we handle that, too, she said. It’s called

The Morphine Drip. It takes about a week. The patients just love it,

she said. They just float away. I asked her if that wasn’t like

helping someone to commit suicide. She answered that they made very

sure that it is the patient who wants it. That seemed an excellent

procedure to me.

I never talked with anyone about this, but I decided that if I ever

had to depend on other people too much, I would go for the morphine

drip. But I was not certain. I was living in a little house whose

bedroom windows faced south. When I got home, I could see the

southern sky when the sun set and the stars came out at dusk every

day. Each day I saw that process, I thought “How beautiful that is.

I want to see another of those.” So maybe I would have stuck around

until the end.

Thank God, I did not have to worry about keeping my job, paying the

bills, or traveling a long way between home and the hospital. I

could do this by myself – and with the docs, modern medicine, and

God.

One day a young doctor was changing the needle in my arm that the

chemicals went through. He had a hard time finding a vein and had

been working 18 hours or so. He stopped and sighed in defeat. I said

to him, “Don’t worry, take your time.” He quietly thanked me. I

thought of one of the last things that Christ said. To another man

on a nearby cross, he said “This very day you shall be with me in

Paradise.” The point being that no matter how far down you are, you

are still able to help other people. That I was able to comfort the

young doc showed me that I was not totally useless.

I dreamed one night that my Grandmother, whose memory I cherish,

walked into my room, looked at me, said “Johnny, you’re not going to

let this slow you down,’ and walked out.

Another day I was walking the halls and passed a young doctor who

had played a small role in my first chemo. I said hello; he asked

how I was; I said fine; and he allowed as everyone was very pleased

at how well I was doing. Happy that my prodigious accomplishments

had been recognized, I made some becomingly modest remark. Then the

doctor asked me if I had made plans for the third operation.

“The third operation?” I asked in quiet shock. Oh, yes, he said,

when we’ve done as much to someone as we’ve done to you, we like to

“re-sect” and see how everything is healing. I asked how soon that

would be. He mentioned a few doctors I should speak to about

scheduling. I told him that I had never heard the names of any of

the doctors he just mentioned. He looked at me and asked “You are

Mr. McDaniels, aren’t you?” I said “No, I’m Mr. Berresford.” He put

his head in his hands and slowly said “I am so sorry.” Great relief

and, again, hilarious. Lucky a gurney didn’t go past as we were

talking!

When I went home after my second long chemo, I was feeling and

showing the effects. I had about half my usual energy; back at home,

one morning I just stayed in bed because I didn’t have the strength

to go downstairs and make breakfast. Just the thought of doing the

dishes exhausted me. The only task I never neglected was taking care

of Sarah. My weight bottomed at 125 pounds (ordinarily I’m 170); I

was bald as a billiard. Shaved heads were starting to become popular

among disaffected youth and some people thought I was a greaser. One

store manager who knew me commented on my baldness as I was buying

something from him. I told him I had cancer. I remember how he

looked at me for a minute. Is this guy going to be alive long enough

to pay the bill?

I put on a shirt one morning and noticed that the neck was more than

an inch bigger than my neck and that the sleeves were almost down to

my fingers. I checked the label; yes, they were from the store where

I bought my shirts. Oh My God, I thought, I’m shrinking! Like Grant

Williams in the 1957 movie! After I calmed down and did some

thinking, I walked to the dry cleaners and found out they had

mistakenly given me the shirts of someone who shopped like me but

was a bit bigger. Major relief.

Some things were getting better. One cold and windy morning I was

walking to work and felt a delicious tingling on my scalp. It was

the first shoots of my post-chemo hair coming in and waving back and

forth in the wind. I had had straight, light brown hair, by the way,

baby fine. My first post-chemo hair came in thick, black and curly;

my first beard came in red. Then things returned to normal.

Most people were extremely sympathetic. One work colleague passed me

on the street and didn’t recognize me. I didn’t notice him, but

later he took the trouble to come to my office and apologize. I

remember only 2 instances of less than perfect sensitivity. One work

colleague said “Oh, cancer. I knew someone who had that. And he

lived two years!” Another person, at a cocktail party for the Human

Rights Campaign Fund, asked about my baldness. I told him I had

cancer and had just finished chemotherapy and the doctors said that

my prognosis was excellent. He replied: “They don’t always tell you

the truth, you know.” I nodded sagely.

The remaining chemo was to consist of two more bags of cisplatin; I

would check in on a Friday afternoon, get the tray of shots and

cisplatin on Saturday morning, be discharged early that evening (if

all went well), and have Sunday to rest before going to work on

Monday. One of the chemo docs said that if I was in a trial in

Pittsburgh, say, I could do all that at a hospital there and be back

in court Monday morning.

Each bag of platinum hurt more and took longer to recover from than

the previous one. Around the time of the third bag, my chemo doctor

told me that the protocol had changed and was now four bags of

platinum, so mark another weekend on your calendar in April. I

shuddered at the thought of another. And asked if it was really

necessary. He said yes. Up to a year ago, he added, the protocol had

been twelve bags. I almost fainted at the thought of what that would

have done to me. They’d have had to take me home on a stretcher.

I puffed myself up and, in my most pompous tone of voice, I said to

the doctor: “I am interested in resuming an entirely normal life at

the earliest possible opportunity.” The doctor leaned forward till

our noses were almost touching and said quietly to me “No . . .

kidding.” I sighed and said “OK, it bring on.”

That last bag was really awful. At the end of it every part of me

hurt – my toenails, my left ear lobe, everything hurt. I went to

Deux Chiminées and couldn’t finish my meal. I just went home, didn’t

think to ask for a doggie bag. But it was over – assuming, of

course, that the cancer didn’t come back.

That was the issue. The cancer had gone away, but would it stay

away? The months that followed were the loneliest and, in a way, the

worst time. Nothing happened. There was no tumor to remove any more,

no numbers to bring down, no heroic first getting out of bed or

surviving the last chemo. There were no crowds cheering in the

stands.

I was supposed to return to normal life. To a large extent I did. I

loved being back in my home, with my dog, my friends, my

neighborhood, and my job.

Every so often, I went back to the hospital for blood tests to see

if the cancer had come back. I’d put down my expensive briefcase

with al the important papers inside, take off my Brooks Brothers

overcoat and suit, put on a hospital smock, and wait in a room with

all the other people waiting for blood tests. It was a humbling

experience to remove all my fancy duds and just be another shlub in

a smock waiting to be told whether he was going to live or die. We

stand naked before God, and in a smock before blood tests.

The test results were always good. At the end of each test, however,

as I put on all my fancy exterior and prepared to walk proudly back

to work down Broad Street to my lawyer job, I knew that all that was

nothing compared to staying alive.

The idea that life was indescribably beautiful, which dawned on me

just after my second operation, eventually grew into a belief that

there had to be a God. Something this complex and gorgeous could not

be the result of random atomic activity. There must be an unmoved

mover.

I had been raised a low church Episcopalian. There was nothing to

hate or fear there – nothing against gays, fortunately – but there

was nothing much to love, either – no passion, no fierce gratitude

for the wonder of the world and my life in it. I found an

Episcopalian Church near where I lived, St. Mark’s at 17th and

Locust. I began attending a short and lightly attended 7:30 AM

service on Tuesday mornings. About my third time there, when the

priest embraced me during the “exchange of peace,” he whispered in

my ear “Give me a cal sometime.” I called him and we made a date for

lunch.

When we got together a few days later, I told him my story (he

probably guessed it because I still looked pretty awful). I asked

him why he had asked me to call him. He said “You looked haunted.” I

told him how dumb I felt having ignored God all these years, or

taken Him for granted. I brought up my gayness by saying that my

life seemed to be falling back into place, and that in fact the

previous weekend was the first one I’d had the strength and

inclination to go out to the bars. He said that he’d seen me on my

way to Equus (a gay bar).

At a pause in the conversation (we’re in the first quarter of 1982),

I asked him if he had heard of this new gay disease that was going

around New York and San Francisco. He shook his head and said how

dreadful it was. I opined that, however bad I was going to be,

ultimately it would be good for us. The explosion of rampant

promiscuity of recent years, though not without its attractions, led

many of us to ignore the emotional and spiritual sides of life.

Bringing our sexual conduct closer to that of heteros would make us

more tolerable to the hetero majority. And showing us as suffering

and caring for each other would present a more sympathetic image of

ourselves to mainstream society than the “sex maniacs and whiners”

image we’d developed. He nodded and said, “This will be our

crucifixion and it will be our resurrection.” I think he was

absolutely right, and I feel that my cancer was the same for me.

Of course, with testicular cancer, I worried about the future of my

sex life. It would be OK to give up sex forever if the alternative

was death. I remember asking the surgeon, at our first meeting,

about the future of my sex life. I don’t remember his answer; I

suppose that means it was neither optimistic nor pessimistic.

I was absolutely limp in the hospital, for both the surgeries and

the chemo. At home after my surgeries, for a while rapid movement of

my genital area was too painful because of all the scars and

still-healing, re-sewn muscles. But eventually the jungle drums

throbbed for human sacrifice, and I joyously discovered that I still

got hard (though not as hard as before) and had orgasms. But nothing

came out.

I took this up with the surgeon in my last post-operative visit. He

said briskly, oh yes, that’s normal. There is a muscle at the base

of the penis, which contracts during orgasm, and that’s what makes

the sperm come out. In the normal case, and yours was unfortunately

normal, he intoned professionally, that muscle is cancerous by the

time of the first operation, so I had to take it out. But you are

still producing sperm, and there are ways of extracting it from you

if you want to have children. And, he added, this muscle has the

strange property of growing back eight or ten years later. And it

gets rather sticky, he said, because these patients come to me and

say “See here, Doc, my wife’s pregnant. Now what’s going on? Is it

me, or is she fooling around?”

I laughed and asked him “What do you say to them?” He broke into a

big smile and boomed out “I say to them, don’t worry, it’s you. It’s

not some [expletive deleted]!’

I went back to The Back Street Baths, a gay sex club a few blocks

from where I lived. I wondered if my almost bald head, only one

ball, and not squirting would be a problem. The sauna room was a

good place to start with small talk. A few guys said “Hi” and I

mentioned that I hadn’t been in the place for a few months. “Why,”

they asked. As I spun out my tale of woe, I got enormous sympathy.

“Oh, my God, you poor guy, welcome back! Is there anything I can do

for you?” Another reason to be grateful for cancer.

By Memorial Day my hair was back to crew cut length and my weight

was above that of a concentration camp survivor. One weekend I was

walking past a sidewalk café on Pine Street and saw one of the young

docs who had worked a bit on my chemo. I stopped for a moment and

said hello. He looked at me blankly and I said “John Berresford.” He

said, “You look like a new person.” I said, “I am, thanks to you”

and walked on.

So, how to sum up?

My

cancer was the best thing that had ever happened to me. Part of me

is a drama and adrenalin junkie, and almost dying of cancer at 31 is

fulfillment beyond one’s wildest dreams. God granted my wish, after

the Judge bowed to me, for a new challenge. I was grabbed, shaken,

and made to realize that life is both fragile and wonderful. Cancer

prepared me for another dramatic life-threatening disease about 5

years later, alcoholism. Cancer was the beginning of a spiritual

life far deeper than any I had had before. It proved to me that I

could survive a major trauma without my biological family. It

separated the sheep from the goats among my friends. Who were the

sheep and who were the goats surprised me, and often disappointed

me. But it’s always better to know the truth. And there were lots of

goats. My

cancer was the best thing that had ever happened to me. Part of me

is a drama and adrenalin junkie, and almost dying of cancer at 31 is

fulfillment beyond one’s wildest dreams. God granted my wish, after

the Judge bowed to me, for a new challenge. I was grabbed, shaken,

and made to realize that life is both fragile and wonderful. Cancer

prepared me for another dramatic life-threatening disease about 5

years later, alcoholism. Cancer was the beginning of a spiritual

life far deeper than any I had had before. It proved to me that I

could survive a major trauma without my biological family. It

separated the sheep from the goats among my friends. Who were the

sheep and who were the goats surprised me, and often disappointed

me. But it’s always better to know the truth. And there were lots of

goats.

I remember seeing an interview with a soldier who fought in The

Battle of the Bulge towards the end of World War II. When asked what

it was like, he said “It was sublime.” I think he meant that it was

everything, A to Z, from the best to the worst, the stars above and

the mud below. That’s what my cancer was. It’s probably a cliché,

but when I was a lot closer to death than I thought I’d be at age

31, I was also more alive than I had been before or have been since.

In closing, a few caveats: all of the foregoing is simply what I

remember, “to the best of my recollection.” I am describing what

happened more than 30 years ago. I probably misremember a few

things. Also, the hospital records were destroyed 25 years after my

disease, so I can’t check my memory against them. I have not

mentioned the names of any of my doctors lest anything I misremember

about our interactions is inaccurate or unfair to them. One thing I

will never forget, however: they were all wonderful and I owe them

my life.

John Berresford |

|

|